I have an addiction. Well, yes, to chocolate, but that’s mostly under control. I am addicted to drawing. I have to draw. My parents fed me a healthy diet of vegetables, fruits, protein, paper, and crayons. Mom said I drew on the walls one afternoon; I never ran out of paper again. Perhaps that explains my inclination to spares. I have a backup of everything from spare keys to art supplies.

Drawing has always come easy. I had an in-house tutor 24-7. My father, William Chambers, has been a professional artist my entire life. I assumed anyone could draw until I went to kindergarten. My first crush was, like Charlie Brown’s, a little red-haired girl who said with such sweetness I remember her blue eyes, Irish chin, and curly locks, “Oh, Tim, you are the best artist.” I was smitten, I think. She asked me to draw often, though she taught me how to scribble a star.

My penchant for drawing increased. Teachers scolded me (“Timmy- no doodling on your assignments!”). When permitted, I turned assignments into art projects; the old adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” held true. Dad was loaded with ideas; for example, for seventh grade American History, Dad directed me (he never did the work) on how to make an American flag consisting of hundreds of faces. I pasted the faces onto the board which I cut into tiles, dyed them red or blue, then assembled them into our flag, representing the great “melting pot” of people that we are. I usually scored well for these projects, likely due more to creativity than content. I

In high school, I was thrilled to discover three large classrooms and teachers that were earmarked for art. My teachers Mr. Pink (yes, I asked and that was/is his real name), Mr. Preo and Mr. Sebastian became my favorite adults. I loved them and they tolerated me, an immature, mischievous kid who set up camp in the art department. And man, did they teach me, feeding me one project after another. They taught me to create lithographs, etchings, silkscreen, linoleum, applique jewelry, silverpoint, photography, and more. I had a college-level experience throughout high school. These men so impacted me and loved on me that we remain in touch forty years later. That incredible high school experience qualified me for numerous national art awards and college scholarships (I blew a 4-year full ride to Washington University in St. Louis, but that’s a story for another post).

While attending university, my father scouted out some of the best painters in the country. Dad made it clear that he was my competition, which tempered my impatience to turn pro. I studied painting for eight years. “You could have been a doctor by now,” a friend said. A miserable doctor, I thought. I have to paint. It was create or die as far as I was concerned.

When I finally had my dad’s and my teachers’ blessing that I was ready for the big leagues of portraiture, I jumped in. You can read more about my training and career start here. My career took off. Commissions came steadily, a portrait agency partnered with me, and awards were coming. In fact, I came in top place at an international portrait competition among 1400 entries. My dream was coming true.

I don’t know about you, but when I hear or read that last line, I think, but…

That but thingy is what makes for great stories, no? Things are looking peachy when the hurricane hits. Or the bad guys or bad news comes knocking. I got the bad news, and it hit me right between the eyes. Or, more precisely, behind the eyes.

Two years after I turned pro, at age 30, a routine eye checkup turned my world upside down. I was diagnosed with Usher syndrome, a disease that would eventually result in my being legally deaf and blind. It was and is a big deal. Life-changing is a gross understatement. I share a snapshot of that journey here.

This disability has not diminished my potential but instead has enhanced it. That’s not the line I was tooting thirty years ago. I was terrified. Again, check out that link for more on that. What I want to share in this post is what this “create or die” artist has learned through this fire. Yes, it has felt like a nonstop fire, testing for the past thirty years.

I have been forced to reexamine my love for art. Art still comes easy for me, per se, just like cooking comes easy for my wife (and not for me). Part of my drive when younger was the dream- or assumption– that I’d be seeing forever and therefore painting. What do you do when a doctor tells you to find another profession because you’ll be deafblind? I had to paint for the now rather than the promise of success.

More important, I began to see that art is more than the visual. It is the awareness and articulation of the things of the heart that make a work of art timeless. I have found that what is unseen is more powerful than what is seen. For years, shop talk centered on translating the visual. Now I judge my work by whether it transcends the soul, evoking the human spirit. We are all striving, to cope with life. Do my paintings communicate the common hope that comes from doing so together? I hope that is what people see when they consider my work.

I have learned that it is not talent that carries great work. Execution is key, of course, but it is the artist and writer that convey the struggles and joys of life from our brush and pen to your mind and heart that make work great. A work that is admirable in execution but lacks the language of a humble and awed heart is stale, void of the human touch. There is a reason we treasure an heirloom dresser over a flawless IKEA piece. Heart, mind, and human touch are the marks we esteem in great art and writing.

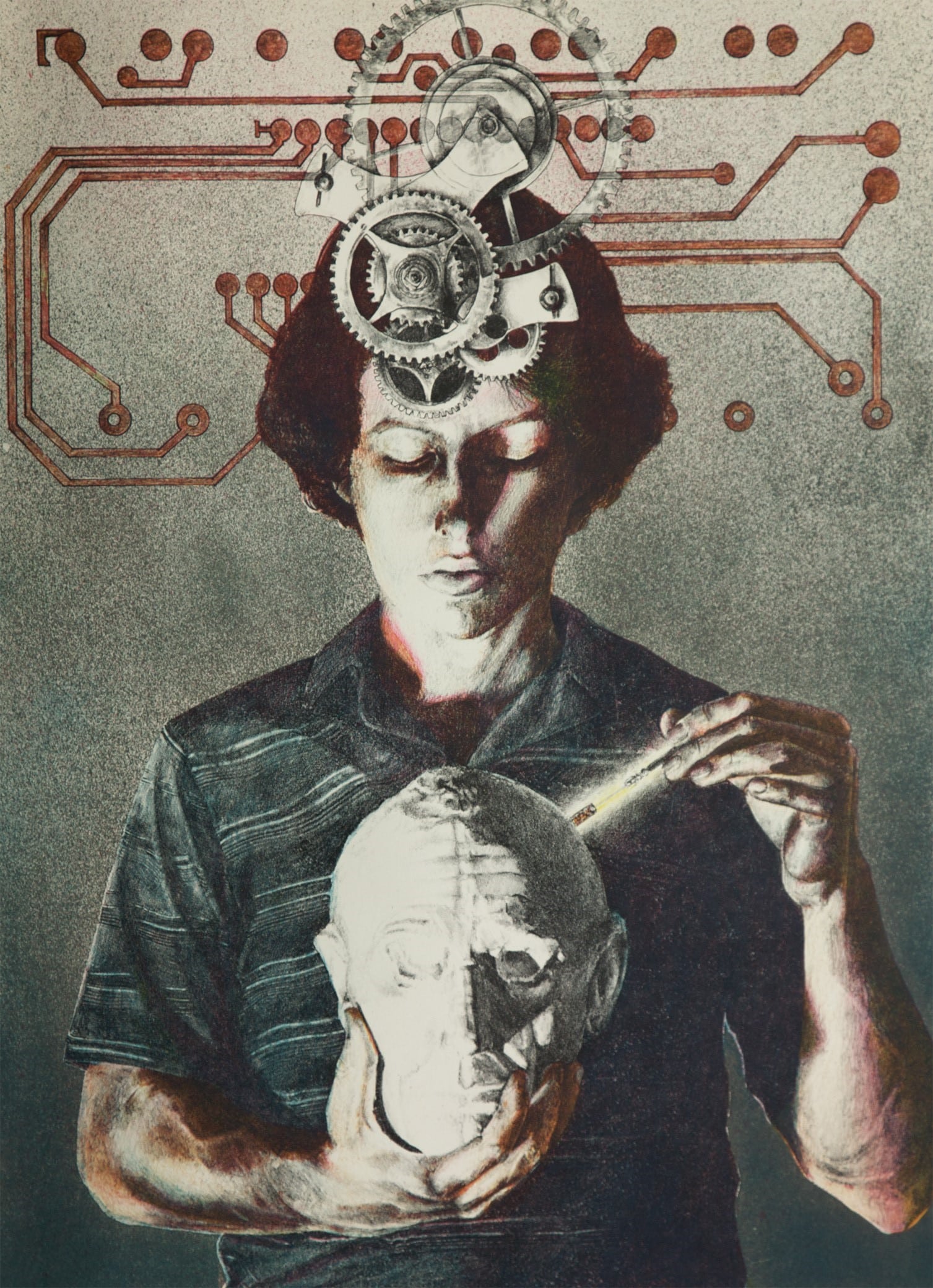

My wife Kim says that Usher has changed me for the better. We hold hands a lot more, though it’s more for safety than romance, I would rather hold her hand than anyone else’s because I (will) love her to death. Kim says that I am more here than I ever was when I was the strapping young, “My future’s so bright I gotta wear shades” man she married. I am still the make-it-happen guy she married, but I am empathetic now. Heart is a key ingredient in my worldview now. Were I to create a lithograph like the Changes above, it would be about the transformation of the heart rather than the mind.