THE USH VIEW

SEEING THROUGH TIM’S EYES

The world through Eyes with Usher Syndrome

Tim has Usher syndrome, a degenerative genetic visual-hearing disease that affects over 400,000 people worldwide. Usher is a combination of Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) and abnormal development of the inner ear’s sound receptor cells. There are at least eleven different subtypes of Ush (Usher) syndrome. Learn more at the Usher Syndrome Coalition (usher-syndrome.com). Tim was diagnosed with Usher Type 2A over twenty-five years ago at the age of 30. Read his story here.

Encouraged by his retinal specialist Hendrik Scholl while working together at Johns Hopkins Wilmar Eye Clinic to “show us what you see,” Tim has been creating a series of paintings and observations to help others grasp the RP experience. This page chronicles that endeavor with comparisons of Tim’s “eyeview” compared to normal vision using paintings, photos, color scales, and more.

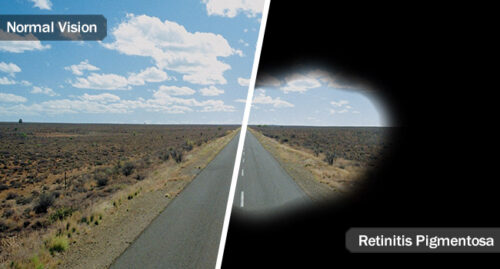

First, let me clarify what someone with RP (Retinitis Pigmentosa) sees.

With the gradual loss of peripheral vision, RP leaves one with what some call tunnel vision, sometimes illustrated like the photo at right. Technically, this is accurate, but practically speaking, it is not.

Why do I say this? Let’s do a little test. Look straight ahead and fix your eyes on an object in front of you. Now, is it black behind you? No, of course not. What is it, then?

This is where your brain fills the gaps. If you’re in a familiar place, you could likely tell me what is in the area beyond your peripheral vision, right? That area is not black; it’s something, and that something is what your brain has filled in with your awareness of your surroundings. Even if you were in an unfamiliar place, such as, say, a restaurant you’ve never been to. Your hearing would provide the clues for your brain to create a 360° visual of your surroundings.

Such as it is for those of us with RP. It’s just that we have to work extra hard to gain that visual. And if we have Usher, combining both the limited vision and hearing, then all the more harder it is for us, as we carefully scan the area, adjust our eyes to varying light intensities, filter out background noise, etc.

This video gives a better idea of what it’s like to deal with diminished peripheral vision:

(Scene 1 – Sight without Usher’s Disease) Yet, it still suggests that the peripheral is a distracting blur of shapes begging for clarity. In reality, your brain offers an imagined, conceptual clarity. In this example, I would have seen the cars on the left a split second ago, and my brain fills that peripheral with an image of a car as I know them to be, not the ambiguous shapes shown in the photo. Same with the grass on the right. I am not left wandering the earth with an ambiguous, vaporous experience!

To bring this home, you have limited peripheral vision as well. A hawk has 270° of peripheral vision- about 90° than humans possess. Does that mean what you don’t see is all fuzzy, leaving you in a funk of uncertainty? No, of course not. That door behind you is still a solid door, and your brain knows it.

With only 17° of peripheral vision, I just have to do a bit more looking around and taking mental notes to size up my surroundings, just as you have to glance around more than that hawk would.

ADJUSTING

A big issue for those with RP is adjusting to various lighting situations. The retina consists of two types of photoreceptors- rods and cones- each serving a distinct purpose. The cones- about 6 million of them, are concentrated in the center and require bright light to provide you with acuity (sharpness) and color information. The 120 million rods are located in the rest of the retina and provide information in lower light than cones do.

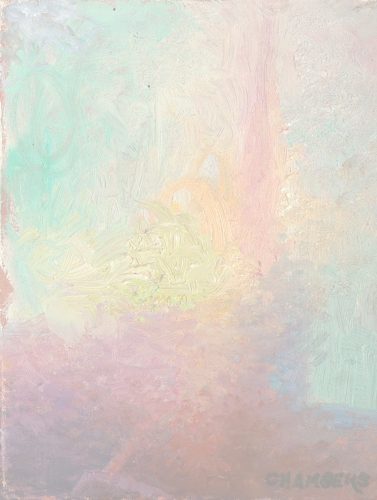

With a lack of rods for low-light situations, and as my retinal specialists have said, a sort of information overload for the center of the retinal, called the macula, people with RP can be temporarily blinded when moving from bright to dim light or vice versa. To illustrate the effect, this is what a color scale looks like to me in such situations:

This (above) is what the scale looks like indoors near a window at noon on a sunny day. Notice the neutral 50% gray background, the bright colors, the rich black, crisp white tones.

This is the same exact scale when I step outdoors into bright sunlight. It takes my eyes about a minute or so to adjust to the bright light. Until then, the scale looks very washed out. Notice that even the black looks grayish, and the four greens are almost the same tone (darkness) as the gray background.

After my eyes have adjusted to the bright sunlight, let’s step back indoors and see how the scale looks to me then.

Wow. The same, beautiful scale with intense colors now looks very dark and grayed. The colors lack any pop (saturation), and even the white looks dingy. Notice the gray background looks dark gray to me. Again, things will return to normal after a minute or two, but until then, I cannot see well indoors except near a bright window or interior light.

If you know someone who has difficulty in adjusting from one light scheme to another, you can serve them by being patient in those moments. Make small talk, casually mention anything to watch out for when you begin walking (“The kids left their bikes right by the steps,” or “The restaurant is crowded tonight! A lot of people in the waiting area.” These are helpful tips and help people like me because we can feel a little trepidatious when our eyes aren’t giving us all the info we depend upon.

SAME STEEPLE, DIFFERENT LOOKS

Inspired by Claude Monet’s series of haystack paintings in which he painted the same subject matter numerous times under different lighting situations, I thought I’d paint a church steeple near my studio. These studies below had to be done in about 15 minutes, as the light was changing so rapidly. I hated having to forego accurate draftsmanship, but my focus here was getting the sense of light and color. These four studies were painted under the following “sun moments”- 1. twilight (sun below the horizon), 2. sunrise (the sun risen, but behind the church and steeple), 3. sun peeking from behind steeple, and 4. the sun high, above the steeple. I painted not how it appears to the normal, healthy eye, but to my eyes at that moment.

USH Steeple Study- Twilight, 5×7″ Oil on Panel

USH Steeple Study- Twilight, 5×7″ Oil on Panel

When the sun is below the horizon in twilight, the scene is lit by a diffused light. For someone like me, with USH, who suffers from glare, this makes things easy to see. What lacks in detail due to the low level of light, is made up for in clarity of edges.

USH Steeple Study- Sunrise, 5×7″ Oil on Panel

The brightening sky of sunrise offers more detail and contrast. Notice that I can readily see the wind vane at the top of the steeple, the shutters at the base of the steeple below the curved roof, and the detail in the gable.

USH Steeple Study- Sun Peeking, 5×7″ Oil on Panel

Whoa- things change quickly as the sun peeks its face from behind the side of the steeple. There is nothing that comes close to the brightness of the sun, and this is like a sudden overload of light to my retina. The glare of the sun obliterates the contours of the steeple and rooflines. It’s as if the sun is spreading yellow pixie dust across the scene, much like we might see all the dust in the air when the sun’s rays shine through an attic window.

USH Steeple Study- Sun High, 5×7″ Oil on Panel

Slowly and steadily contours return as the sun rises higher into the sky. Because the sun is not in the scene, but above the view, the glare is greatly reduced (you know how we shelter our eyes when someone is standing in line with the sun). Yet the glare from the sun’s brightness remains and the top of the steeple is shrouded by the sun’s “pixie dust.”

The painting at right, A New Day,shows how the bright glow of the morning sunlight diffuses the contours of the trees and chimneys. People with normal vision might see these objects’ contours sharply defined, but for Tim, the effect of reduced photoreceptor cells affects the silhouetted definition of objects in front of a bright light. By comparison, notice the sharp detail of the leaves in the foreground. Tim is able to see these with clarity due to the lesser light in that area of the scene.

The painting at right, A New Day,shows how the bright glow of the morning sunlight diffuses the contours of the trees and chimneys. People with normal vision might see these objects’ contours sharply defined, but for Tim, the effect of reduced photoreceptor cells affects the silhouetted definition of objects in front of a bright light. By comparison, notice the sharp detail of the leaves in the foreground. Tim is able to see these with clarity due to the lesser light in that area of the scene.

As you can see, the effect that USH has on one’s vision is complex. It is not the simplistic and inaccurate illustration of tunnel vision (an all-black visage with a peek-through hole in the middle). Our brains are a marvelous creation that more than makes up for what we lack.

When you encounter an unfamiliar situation, what do you do? Your brain instantly goes to work, gather all past information to present a list of possible options to help you assess the situation and moment before you. Suddenly, a picture comes to mind; your mind has filled in the blanks of the unknowns. You will tweak these assumptions as you gather current info, but nonetheless, you are not clueless at the moment. You have an idea of what’s happening, even if you really don’t actually know all the present details. It’s a very good survival mechanism, for your mind is using your brain’s incredible resources and memory to prepare you for this moment.

In much the same way, that’s how things work for those of us dealing with some sort of blindness. When I awake in the middle of the night, I may (nor you) may see what’s on your nightstand, but you know.You’ve seen the items a thousand times; you know what’s there, from the stack of book titles to the tube of Chapstick and the Bic pen beside them. You know where the buttons on the clock are, you know where to reach for the lamp switch. All this in pitch darkness. You don’t see, but you know.

This same process works for me a million times throughout my day. What’s lacking in my peripheral vision is filled in by my mind to create a complete picture. There is no black void.

HOW CAN I POSSIBLY PAINT PORTRAITS?

You may be wondering, per the steeple studies above, how can I possibly create finished works such as my portraits? That’s a good question! There are four aspects I make use of to compensate for what I lack: adjusting, scanning, memory, and experience.

You may be wondering, per the steeple studies above, how can I possibly create finished works such as my portraits? That’s a good question! There are four aspects I make use of to compensate for what I lack: adjusting, scanning, memory, and experience.

Recall in our discussion about the color scales that I mentioned that my eyes adjust after a minute or so. When I initially step outside into bright sunlight, yes, it’s overwhelmingly bright, kind of like if you were in a pitch dark room and I shined a flashlight into your eyes. However, after a few moments, our eyes adjust to the level of light in the scene. The same goes for the reverse, such as stepping into a dark pub from the street at noon on a sunny day. Initially, it is very hard to see, but our eyes adjust.

When I am painting, I see only a small area at a time. I make up for this in two ways: scanning and experience. The visual field kind of operates like a cone; the visual field expands as distance increases. Standing next to you, I may only see part of your face. Take a few steps back, now I see your head and torso. A few more steps and now I see your entire figure.

Even when my vision was normal, I’ve always painted standing up in order to step back and take in my entire canvas. This is common practice for many painters. Thus, when I am working up close on a painting, I am aware of the entire painting. Thus, I am making use of scanning (stepping back and taking in the entire painting) and memory (remembering what I just saw). All artists paint from memory. When we look at, say, a church steeple, and observe, we are noting and memorizing. Then we turn to our canvas and paint from memory what we just saw. Even with limited vision, I am merely doing what I’ve been doing my entire life! Nothing new here.

Experience is the fourth aspect that plays into creating my paintings. I have a lifetime of experience creating art. I know. I know what to do to make a painting look beautiful. I know anatomy. I know the principles of form and color and values. When I was a student, I could barely think of two or three principles at a time. Now I instinctively incorporate numerous principles into every stroke. I am a master at what I do.

CONCLUSION

In all honestly, it is truly fascinating how we make use of any and all resources to live and survive. Human ingenuity is marvelous to behold. We adapt. People who hear what I am working with- less than 10% of normal vision!- are amazed at what I can do. Heck, I still play tennis competitively (that’s another story). But in my mind, I have simply analyzed my limitations and creatively adapted. It’s almost a game to me- find a solution to this problem. My kids know never to tell me a task is impossible, as I take it as a challenge to do the impossible!

If you’d like to learn more about Usher syndrome, I invite you to visit Usher Syndrome Coalition. If you have questions about what I have shared or would like to share your own experiences with limited vision, please contact me. I’d love to hear from you.

Usher Syndrome Fact Sheet

- Diagnosis: Usher Syndrome is diagnosed by hearing, vision, and balance tests.

- Causes: Specific gene mutations.

- How many people have Usher Syndrome? Around 3-10 per 100,000 people.

- Types of Usher Syndrome

- Type 1: Profound hearing loss and balance issues in early childhood

- Type 2: Hearing loss at birth, vision depreciation beginning in the late teens to early 20s.

- Type 3: Hearing and vision reduction starting in the 20s – 40s.

- Treatments: Therapies are coordinated on an individual patient basis.